The advent of online commerce, made possible by technology and epitomized by Amazon.com, eBay, iTunes, and Netflix, has led to a shift in consumer buying patterns, according to Chris Anderson, author of The Long Tail.

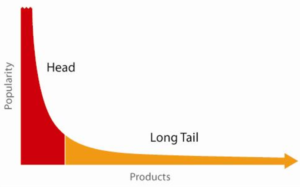

In most markets, the distribution of product sales conforms to a curve weighted heavily to one side—the “head”—where the bulk of sales are generated by a few products.

The curve falls rapidly toward zero and hovers just above it far along the X-axis—the “long tail”—where the vast majority of products generate very little sales. The mass market traditionally focused on generating “hit” products that occupy the head.

Anderson says the Internet is shifting demand “down the tail, from hits to niches” in a number of product categories including music, books, clothing, and movies. His theory is based on three premises:

- Lower distribution costs make it economically easier to sell products without precise demand predictions;

- the more products available for sale, the greater the likelihood of tapping into latent demand for niche tastes unreachable through traditional retail channels; and

- if enough niche tastes are aggregated, a big new market can result.

Although some research supports this theory, other research finds very low share products may be so obscure that they disappear before they can be purchased frequently enough to justify their existence. For companies selling physical products, inventory, stocking, and handling costs can outweigh any financial benefits of such products.