New Product Development

The stages in new product development are shown in Figure 9.2 and discussed next.

1 Idea Generation

The new-product development process starts with the search for ideas. Some marketing experts believe we find the greatest opportunities and highest leverage for new products by uncovering the best possible set of unmet customer needs or technological innovation. Ideas can come from interacting with customers, employees, scientists, and other groups; from using creativity techniques; and from studying competitors. Through Internet-based crowdsourcing, paid or unpaid outsiders can offer needed expertise or a different perspective on a new-product project that might otherwise be overlooked. The traditional company-centric approach to product innovation is giving way to a world in which companies co-create products with consumers. Besides producing new and better ideas, co-creation can help customers feel closer to the company and create favorable word of mouth.

2 Idea Screening

The purpose of screening is to drop poor ideas as early as possible because product-development costs rise substantially at each successive development stage. Most com-panies require new-product ideas to be described on a standard form for a committee’s review. The description states the product idea, the target market, and the competition and estimates market size, product price, development time and costs, manufacturing costs, and rate of return. The executive committee then reviews each idea against a set of criteria. Does the product meet a need? Would it offer superior value? Can it be distinctively advertised or promoted? Does the company have the necessary know-how and capital? Will the new product deliver the expected sales volume, sales growth, and profit? The committee estimates whether the probability of suc-cess is high enough to warrant continued development.

3 Concept Development and Testing

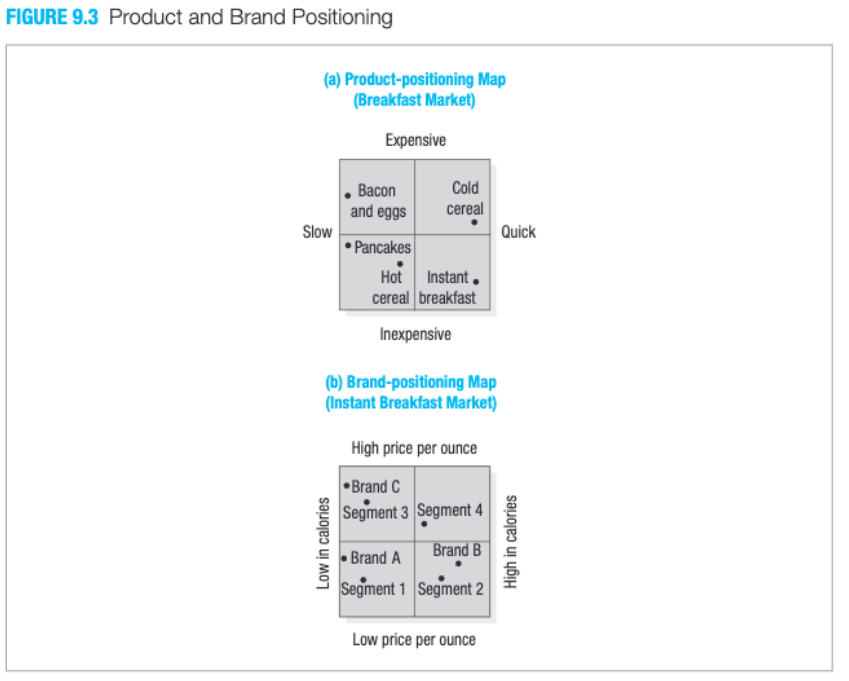

A product idea is a possible product the company might offer to the market. A product concept is an elaborated version of the idea expressed in consumer terms. A product idea can be turned into several concepts by asking: Who will use this product? What primary benefit should this product provide? When will people consume or use it? By answering these questions, a company can form several concepts, select the most promising, and create a product-positioning map for it. Figure 9.3(A) shows the positioning of a product concept, a low-cost instant breakfast drink, based on the two dimensions of cost and preparation time and compared with other breakfast foods. These contrasts can be useful in communicating and promoting a concept to the market.

Figure 9.3 (b) is a brand-positioning map, a perceptual map showing the current positions of three existing brands of instant breakfast drinks (Brands A–C) as seen by consumers in four segments, whose preferences are clustered around the points on the map. The brand-positioning map helps the company decide how much to charge and how calorific to make its drink. As shown on this map, the new brand would be distinctive in the medium-price, medium-calorie market or in the high-price, high-calorie market. There is also a segment of consumers (4) clustered fairly near the medium-price, medium-calorie market, suggesting this may offer the greatest opportunity.

Concept testing means presenting the product concept to target consumers, physically or symbolically, and getting their reactions. The more the tested concepts resemble the final product or experience, the more dependable concept testing is. In the past, creating physical prototypes was costly and time consuming, but today firms can use rapid prototyping to design products on a computer and then produce rough models to show potential consumers for their reactions. Companies are also using virtual reality to test product concepts. Consumer reactions indicate whether the concept has a broad and strong consumer appeal, what products it competes against, and which consumers are the best targets. The need-gap levels and purchase-intention levels can be checked against norms for the product category to determine whether the concept appears to be a winner, a long shot, or a loser.

4 Marketing Strategy Development

Following a successful concept test, the firm develops a preliminary three-part strategy for introducing the new product. The first part describes the target market’s size, structure, and behavior; the planned brand positioning; and the sales, market share, and profit goals sought in the first few years. The second part outlines the planned price, distribution strategy, and marketing budget for the first year. The third part describes the long-run sales and profit goals and marketing-mix strategy over time. This strategy lays a foundation for the business analysis.

5 Business Analysis

Here the firm evaluates the proposed product’s business attractiveness. Management needs to prepare sales, cost, and profit projections to determine whether they satisfy company objectives. If they do, the concept can move to the development stage. As new information comes in, the business analysis will undergo revision and expansion. Sales-estimation methods depend on whether the product is purchased once (such as an engagement ring), infrequently, or often.

For one-time products, sales rise at the beginning, peak, and approach zero as the number of potential buyers becomes exhausted; if new buyers keep entering the market, the curve will not drop to zero. Infrequently purchased products such as automobiles exhibit replacement cycles dictated by physical wear or obsolescence associated with changing styles, features, and performance. Therefore, sales forecasts must estimate first-time sales and replacement sales separately. With frequently purchased products, such as consumer and industrial nondurables, the number of first-time buyers initially increases and then decreases as fewer buyers are left (assuming a fixed population). Repeat purchases occur soon, providing the product satisfies some buyers. The sales curve eventually falls to a plateau of steady repeat-purchase volume; by this time, the product is no longer a new product.

6 Product Development

Up to now, the product has existed only as a description, drawing, or prototype. The next step represents a jump in investment that dwarfs the costs incurred so far. The company will determine whether the product idea can translate into a technically and commercially feasible product.The job of translating target customer requirements into a working prototype is helped by a set of methods known as quality function deployment (QFD). The methodology takes the list of desired customer attributes (CAs) generated by market research and turns them into a list of engineering attributes (EAs) that engineers can use. For example, customers of a proposed truck may want a certain acceleration rate (CA). Engineers can turn this into the required horsepower and other engineering equivalents (EAs). QFD improves communication between marketers, engineers, and manufacturing people.

The R&D department develops a prototype that embodies the key attributes in the product-concept statement, performs safely under normal use and conditions, and can be produced within budgeted manufacturing costs, speeded by virtual reality technology and the Internet. Prototypes must be put through rigorous functional and customer tests before they enter the marketplace. Alpha testing tests the product within the firm to see how it performs in different applications. After refining the prototype, the company moves to beta testing with customers, bringing consumers into a laboratory or giving them samples to use at home

7 Market Testing

After management is satisfied with functional and psychological performance, the product is ready to be branded with a name, logo, and packaging and go into a market test. Not all companies undertake market testing. The amount of testing is influenced by the investment cost and risk on the one hand and time pressure and research cost on the other. High-investment–high-risk products, whose chance of failure is high, must be market tested; the cost will be an insignificant percentage of total project cost. Consumer-products tests seek to estimate four variables: trial, first repeat, adoption, and purchase frequency. Table 9.3 shows four methods of consumer-goods testing, from the least costly to the most costly.

Expensive industrial goods and new technologies will normally undergo alpha and beta testing. During beta testing, the company’s technical people observe how customers use the product, a practice that often exposes unanticipated problems of safety and servicing and alerts the company to customer training and servicing requirements. At trade shows the company can observe how much interest buyers show in the new product, how they react to features and terms, and how many express purchase intentions or place orders. In distributor and dealer display rooms, products may stand next to the manufacturer’s other products and possibly competitors’ products, yielding preference and pricing information in the product’s normal selling atmosphere. However, customers who come in might not represent the target market, or they might want to place early orders that cannot be filled.

8 Commercialization

Commercialization is the costliest stage in the process because the firm will need to contract for manufacture, or it may build or rent a full-scale manufacturing facility. Most new-product campaigns also require a sequenced mix of market communication tools to build awareness and ultimately preference, choice, and loyalty. Market timing is critical.If a firm learns that a competitor is readying a new product, one choice is first entry (for “first mover advantages” of locking up key distributors and customers and gaining leadership). However, this can backfire if the product has not been thoroughly debugged. A second choice is parallel entry (timing its entry to coincide with the competitor’s entry to gain both products more attention). A third choice is late entry (delaying its launch until after the competitor has borne the cost of educating the market). This might reveal flaws the late entrant can avoid and also show the size of the market.

Most companies will develop a planned market rollout over time. In choosing rollout markets, the major criteria are market potential, the company’s local reputation, the cost of filling the pipeline, the cost of communication media, the influence of the area on other areas, and competitive penetration. With the Internet connecting far-flung parts of the globe, competition is more likely to cross national borders. Companies are increasingly rolling out new products simultaneously across the globe